This may seem like an obvious place to start but I think it is worth mentioning that I have had some students with a vision impairment who have found the very concept that music is written down difficult to grasp. We must never underestimate the importance of incidental learning and so most of the students that I work with will never have actually seen print music. Certainly any tactile representation of print music is far too cluttered with crisscrossing lines to be at all discernible to the touch. Tactile representation of print music is a non starter, however, I do quite a lot of work with my younger students based on tactile graphics. Before I explain how and why I do this, let’s consider how a fully sighted musician accesses print music.

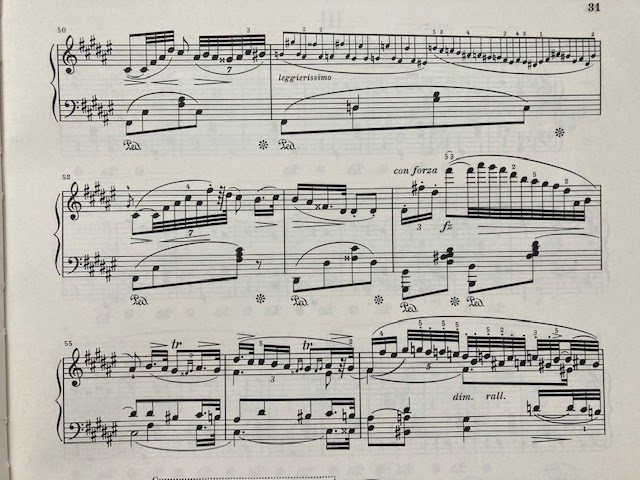

Below is a picture of some print music for piano from a Chopin prelude.

At first glance the sighted musician would see that this music looks difficult and busy. We’d say the music looks “very black” meaning that there is a lot of black ink on the page as a result of lots of short notes all beamed together with detailed performance directions and articulation – never mind the actual notes. The way that the music is presented gives us some clues as to how to decode it. The notes within a beat are beamed together so we can map out where the notes lie in relation to the beat and the parts neatly overlap so that we know which notes coincide with each other. We learn to recognise the shapes of different chords so that we don’t need to read every note and of course, we can see the melody line moving up or down and a leap is obvious. Although the complexity of this music would make it difficult to sight read, a skilled pianist would be able to get a sense of the general gist on the first reading because the eye can scan a lot of information in one go. It is certainly possible to read and play simultaneously and a sighted musician would not need to commit everything to memory because the print notation is pictorial and serves to remind the musician in real time as they play through the piece.

The same cannot be said for music represented by braille with its uniformity of size and no immediately obvious clues as to how it all fits together. Firstly, we need to bear in mind that it is not possible to read and play at the same time, even if a person had four hands! The braille music code is completely linear and requires a certain amount of piecing things together. Having said that, it is a brilliant and logical code. It does pretty much everything that can be done in print music. I say pretty much, because it may struggle with some of the weird twentieth century signs which haven’t really stood the test of time but I’m not overly concerned about that.

The approach of the braille reader is to go straight into detail rather than see a general gist of things. The same is true of any tactile learning as the learner needs to piece together what lies under the finger. The other thing, of course, is that it will need to be memorised and that’s a whole issue in itself. Many of my students are quite bemused that sighted folk rely so much on reading music when playing.

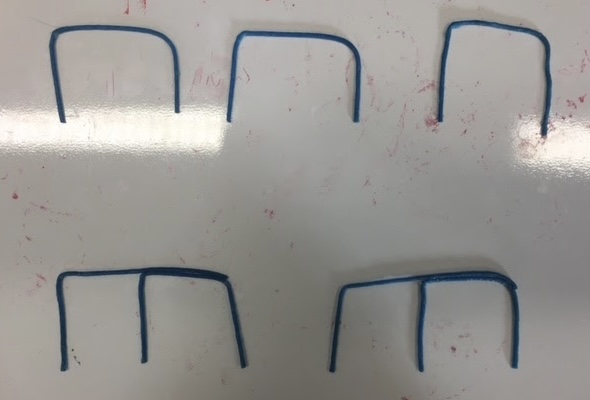

So, why do I introduce my students to tactile graphic symbols by way of introduction to learning to read music? Well, one thing I have found is that my students are usually fantastic when it comes to pitch but the process of interpreting rhythm is relatively difficult and this, of course, is a key element of reading music. They are very good at copying a rhythm presented aurally, by and large, but working out the rhythm of a notated melody with subdivisions of beat and knowing what goes where does involve a certain amount of mental mapping and so I often use kinaesthetic methods to try and reinforce this. Below is a picture of a white board with flexible wax sticks (Benderoos or Wikki Stix) which are great for making tactile graphics on the fly. Here, I have aimed to show a student the difference between 6/8 and 3/4. You can do similar things with 6 pencils, repositioning in 2 groups of 3 and then 3 groups of 2 and I always include a certain amount of clapping and marching on the spot whilst counting out loud to further reinforce the concept.

More to come on this and other things relating to teaching music to children and young people with a vision impairment. I certainly don’t regard myself as an expert. It’s a word I dislike because I feel as if I still have a lot to learn. You never stop learning in this game and the students keep me on my toes. What I do know is that when you are new to it all, it can be a bit daunting and so even if I only help a handful of people by writing these posts then it will have been worth the effort.